Indiana University’s Mangilal Agarwal believes he has found the key to earlier prostate cancer detection; a grant from the American Cancer Society – and an assist from some four-legged friends – are vital to the effort.

Michael Haggard waited anxiously as Indiana University’s Mangilal Agarwal and a team of physicians brought his sample to the highly advanced testing equipment that would help determine whether he had prostate cancer.

This technology relies on 300 million receptors to conduct an analysis 50 times more precise than what could ever be done by a human. Its early-detection ability could mean the difference between life and death for Haggard and the more than 200,000 men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer each year.

But this technology has nothing to do with artificial intelligence (AI). It doesn’t need a server or the cloud. It doesn’t even run on electricity. All this cutting-edge technology needs is a treat, the occasional scratch behind the ear, and a good walk at the end of a long day.

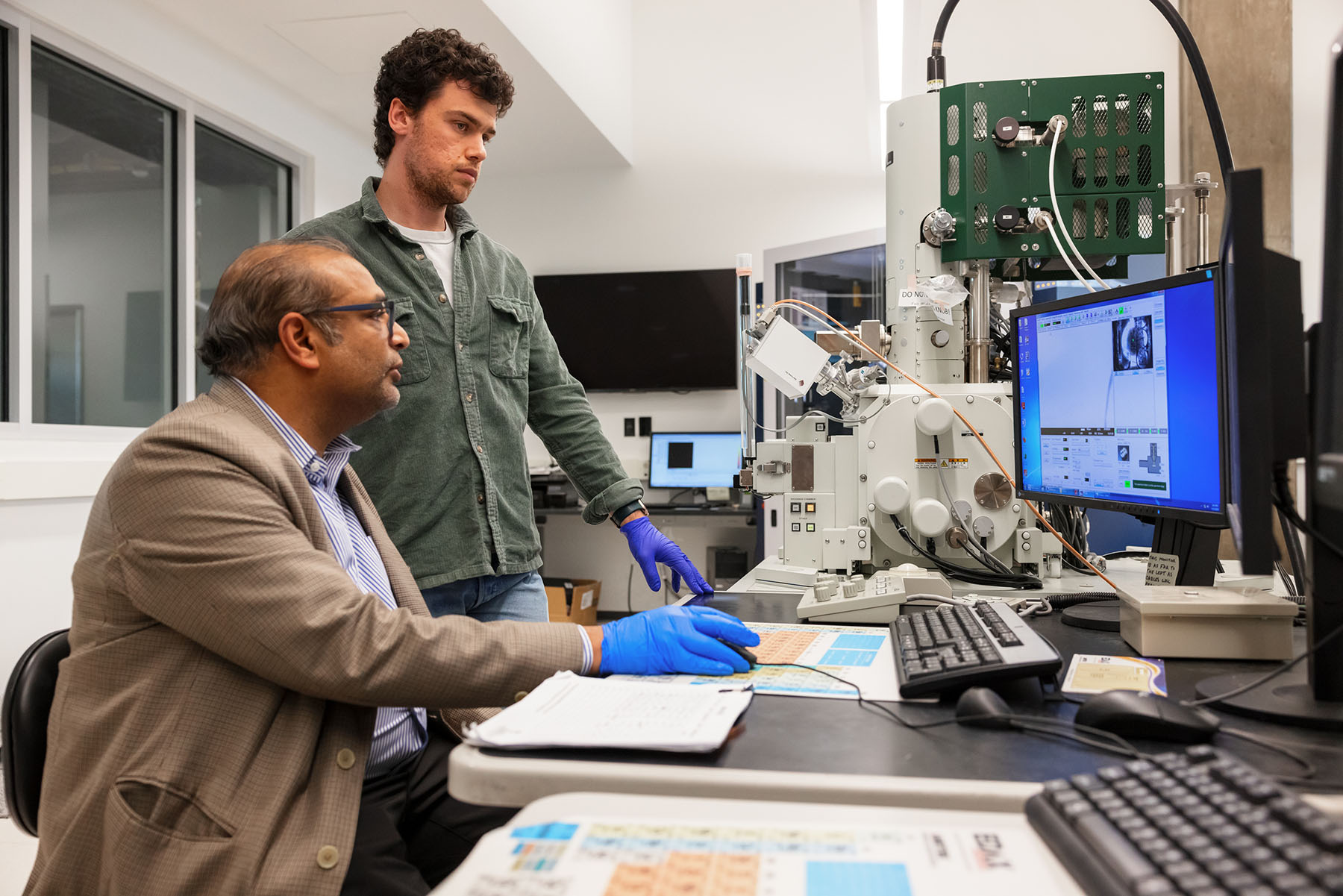

Agarwal is the founder and director of the Indiana Nanotechnology Development Institute (INDI) . He also serves as a professor of biomedical engineering and informatics at Luddy Indianapolis . He and his team of students and fellow researchers are on the scent of a new way to test for prostate cancer, and he’s leaning on man’s best friend to help make it happen.

Inside the need for a new test

The current screening method involves a blood draw and is called a prostate-specific antigen test, or PSA. The problem is that PSA tests falsely come back positive between 15% and 75% of the time and fail to detect existing prostate cancer in 15% of cases.

That miss rate creates unnecessary worry and equally unnecessary prostate biopsies for the false-positive patients. Worse, it can have lethal consequences in those whose tests incorrectly come back normal. Early-stage prostate cancer is 100% curable. Later-stage prostate cancer is 100% incurable.

Enter the dogs.

Around a decade ago, Agarwal was perusing a medical journal when he read research from a study in Italy that detailed how canines could detect prostate cancer with 98% accuracy by smelling patients’ urine samples. A 98% detection rate provides a better chance of survival for 13% of the 15% of men the current PSA test misses, and so Agarwal got to work.

A dog’s nose has up to 300 million olfactory receptors, compared to a human’s 6 million. That gives canines an advantage is sniffing out everything from that dropped piece of steak to, Agarwal hopes, prostate cancer.

“As an engineer, I thought, OK, there must be some unique molecules they’re smelling, some specific volatile organic compounds unique to prostate cancer. If we could identify those compounds, then we could engineer a technological solution,” says Agarwal, who earned his PhD. in engineering with a micro/nanotechnology concentration in 2004.

Agarwal joined IU Indianapolis in 2009 as the associate director for research development in the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research. Since then, he has been working to find the infinitesimal signals diseases might give off that could lead to earlier detection.

Indiana University Changing Lives through Research: Prostate Cancer

Description of the video:

If prostate cancer is diagnosed early,it is 100% curable. If it's diagnosed late,

it can be 100% uncurable. >> They say there's no symptoms,

so you don't really know, so I was hoping it wasn't cancer. But on the other hand, if it was, I wanted

them to be able to do something about it. >> It is a disease that we

have the ability to screen for currently using a blood

test currently called PSA. This is not a very good test in the sense

that it tells us something's going on in the prostate, but doesn't actually tell

us what's going on in the prostate. >> They went in and did biopsy, and they

had to put me on some more medicine, and they said let's see where this takes you. I'll be 68 next month, and I'm glad I

did it because my dad died of cancer. So when I retired, I thought well

I don't wanna be two years out and die because of something stupid. >> There was a recent study

that dogs can sniff urine and can tell whether the patient

has prostate cancer or not. So the big question that we

are exploring is is what is that smell? We collaborated with VA to

get these urine samples. >> We work with the urology clinic and

the veterans who are scheduled for biopsy are invited to join the study and

donate urine before their biopsy. >> They said they were doing a study for

IU. They told me that they were doing it for

the dogs to be able to sniff out prostate cancer, kind of groundbreaking

>> We are already collaborating with a dog trainer in town

who trains medical dogs. The idea is to verify

the signature that we identified in the lab with the dogs in the field. >> We get our samples from Mangi and

Amanda from IU. Once we have the samples,

we present them to the dogs, and we teach our dogs to look for the specific

sample that they need to detect. Everything is visually identical, and the dog only has the option to

use his nose to find the sample. The way that we have taught the dogs to

indicate that they have found a sample in a can is to maintain their head inside

the can until we dispense the treat. >> Of course, we can do 100 things in the

lab, and we can say this is the biomarker. If we know what signature it is and if we can verify that signature with

a trained dog, then we feel that there will be a speedy acceptance

of the results in the community. >> We go to the VA,

we pick up the urine samples, we bring them back to the lab,

and then we incubate them with a polymer-based fiber which is very

good at collecting the scent of the urine on to the fiber because our

noses are not as good as the dogs. >> So the end goal is have

a prostate cancer sensor that can be used in a doctor's office to test

prostate cancer in real time. Since it's noninvasive,

it just needs urine sample. So once we have this sensor, the goal

is to increase widespread screening. >> Work with sense is something that we're

just on the beginning of understanding how important it is. In the the next ten years, we'll see

a big explosion in this type of research.

Partnerships and grants

Angarwal’s work reflects partnerships across Indiana University. It relies, for example, on urine samples from prostate cancer patients collected in collaboration with physicians such as Dr. Thomas Gardner , a professor of urology and of microbiology and immunology at the IU School of Medicine . He serves patients at the Richard L. Roudebush VA Hospital in Indianapolis.

That’s where Angarwal and his team met Haggard, a U.S. Army veteran.

Men visiting the VA hospital for biopsies to detect prostate cancer are given the opportunity to join the olfactory study. For Haggard, it made sense. “It’s kind of groundbreaking, ya know,” he says. “I was hoping it wasn’t cancer, but if it was, I wanted them to be able to do something about it.”

Patients’ samples are taken to a lab and put in a polymer-based fiber ideal for soaking up scent. One sample that is positive for prostate cancer is then put for dogs-in-training inside one of an array of identical metal cans. When dogs put their head in the right can, a treat is dispensed, reinforcing the desired behavior.

It’s not just Agarwal and his team who believe in the promise of better prostate detection through man’s best friend. In September, the American Cancer Society awarded Agarwal a $1.2 million grant to further his research.

Through that grant, Agarwal’s lab will be able to not only confirm they have identified the correct compounds that indicate prostate cancer but transition their results onto a sensor for a portable system that doesn’t need food, water, or flea-and-tick protection. The hope is these portable systems will become a non-invasive way to screen for prostate cancer in real-time at clinics — or even at home.

Agarwal is clear on the mission. “Once we have this sensor," he said, "the goal is to increase widespread screening.”

Reversing a negative trend

That widespread screening grows more necessary every year. Prostate cancer numbers were retreating from 2007 to 2014 , but Agarwal and the American Cancer Society say that was because of changes in screening guidelines that pushed back the recommended starting age for testing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, the incidence rate of prostate cancer has increased by 3% per year since 2014 . Worse, that increase is 5% per year for advanced-stage prostate cancer. The American Cancer Society’s data shows that nearly 300,000 new cases of prostate cancer will be diagnosed in 2024, and more than 35,000 men will die from the disease.

Prostate cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death in American men, behind only lung cancer. The death rate declined by about half from 1993 to 2013, according to data from the American Cancer Society, most likely due to earlier detection and advances in treatment.

An easy, painless test would both reduce these hardships as well as increase the number of people who are getting screened, reducing deaths from the disease.

Mangilal Agarwal

But in recent years, the death rate has leveled off and threatens to start climbing again. Agarwal believes an easier, non-invasive, and more accurate screening will stop that rise from happening and could also lead to a new drop. The American Cancer Society’s grant is a major factor in that hope, he says.

“Over the next five years, we expect to produce a comprehensive strategy to translate this technology to the consumer market,” he says. “There are both too many false positives and not enough people getting screened due to the fear of needing a biopsy. An easy, painless test would both reduce these hardships as well as increase the number of people who are getting screened, reducing deaths from the disease.”

That holds true for men like Haggard, whose test was, indeed, positive.

“I (didn't) want to be two years out from starting my retirement and die because of something stupid that was curable," he says. “I’m glad I am part of this effort.”